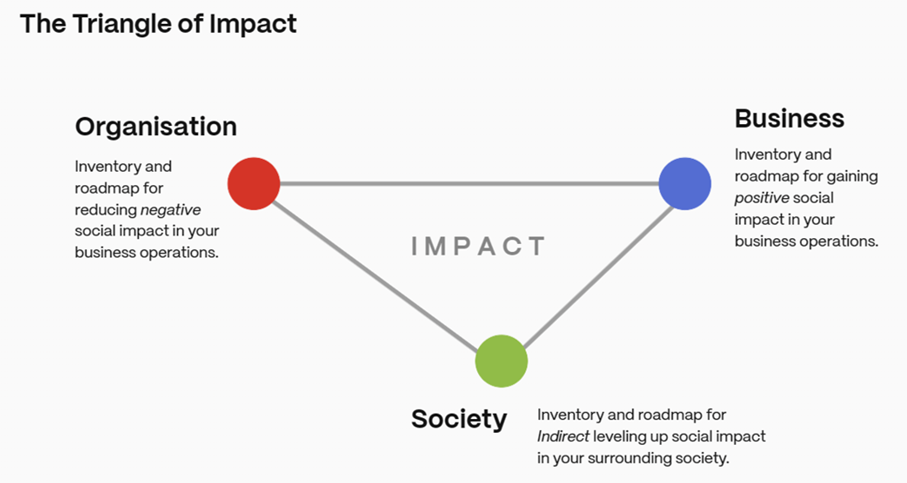

Triangle of Impact

How do you measure and manage towards social sustainability? We have given it a try and created a tool that we call the Triangle of Impact

This is a slightly different post, so a brief background on my interest in these issues may be in order, but I have put it at the end of the document for those who are interested. *

For some time now, together with some companies that want more, I have been working on a model, or tool, for social sustainability. Those of us who have worked with this tool are the pharmaceutical company Chiesi Pharma, Tobii Dynavox (which is a leader in communication aids for people with communication challenges) and the communications agency Spoon. In addition, we’ve been privileged to have had a few more people and companies providing wise input. And then there’s We-ness (David Wiking), who facilitated the process.

The purpose of the tool is to help companies both report – and communicate – and to manage their operations towards a higher degree of social sustainability. When we started the work, we agreed on three starting points. The tool:

- Should be easy to use, yet effective. Limit the number of “nice-to-have” questions/features.

- Will focus in particular on the positive impact companies can have, in addition to “hygiene factors”

- Should be based on other information that the company either already discloses, or will need to report. This applies in particular to the requirements that follow from the EU Sustainability Reporting Regulation (CSRD) and its four standards on social sustainability (S1-S4 and possibly G1)

We also talked about a fourth starting point: the tool should facilitate cooperation between companies that allows good ideas to spread – and exchange. It is doubtful if we have reached that point yet, but the ambition remains.

This tool is not only (or primarily) intended for so-called “solution companies”, but on the other hand, the tool is probably most useful for companies that actively pursue value not only for owners but also for other stakeholders – i.e. the fairly large group of companies that believe that in addition to returns, they also have or want to have a positive impact on people or planet.

We divided positive impact into direct and indirect impact, where the big difference is that the indirect impact is a side effect, rather than the result of an active choice. This is not to say that the indirect impact cannot be addressed, but as the company strives to actively increase its indirect impact, the impact also becomes more direct in nature. In addition to direct and indirect impact, we considered it important that the tool should help limit the company’s own negative impact, which thus became a third category of impact. The model below summarizes the different categories, which we also think of as “scopes” for social sustainability.

1. Your own organization: how can you reduce the negative impact and instead achieve something positive? (Scope 1)

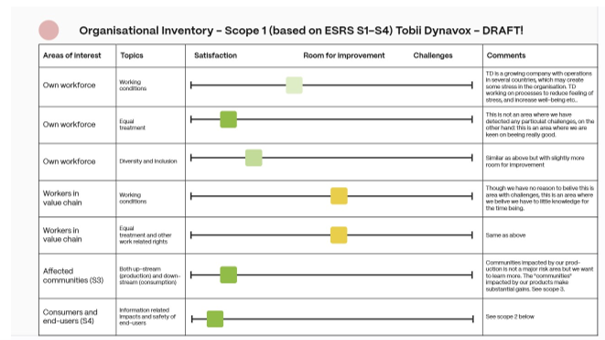

In this scope, we ask ourselves how the company relates to its employees, its suppliers and, at least in part, its customers. The questions are based on the standards for social sustainability that have been developed for reporting, according to the EU’s CSRD directive, so for those companies that have already made a double materiality assessment, there is a good base line – and for those who have not, this can assist in future reporting. Unlike in the materiality assessment, here we have shifted the focus from mainly reporting your impact, to what you actually want to do to improve. In this way, this becomes both a way to account for the gaps that exist, and a way to consider if the company is satisfied with the status que, or wants to strive for an improvement (since a gap is not necessarily the same as an area where you want to improve).

Below is an example, a snapshot, of what this assessment might look like at an early stage (Note that the data is not validated):

This way of approaching the impact is a way of taking the materiality assessment a step further: the issues that are reported are chosen because they are important (material) to the company, but what emerges above all in this scope, is whether you intend to do something about the various issues that are raised. In this way, it becomes a way to reflect in a structured way on what you think you want and can do something about.

2. The conscious, positive impact that the company has – can have – through product and operations (Scope 2)

Most frameworks and regulations are about limiting the negative impact of companies, about doing as little significant harm as possible. It’s not as strange as it sounds; Human rights, for example, are primarily about the responsibility of states towards their citizens. Strictly speaking, it is not the responsibility of companies to ensure that people have, inter alia, freedom of expression or the right to education. On the other hand, companies do not have the right to deprive people of their rights. In practice, of course, many companies also play a crucial role in enabling people to fulfil their human rights.

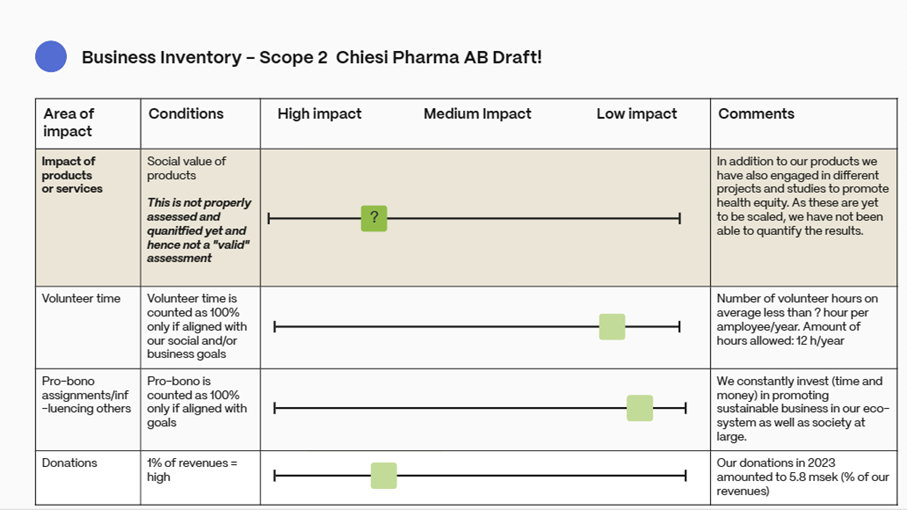

This scope is about documenting the positive role that the company has. This gives you the opportunity to reflect on your positive impact, to show others what you do and to create a “base-line“, so that you can compare with yourself over time, and perhaps also with other companies. Below is an example of what this might look like: (please note that the data in the example are not fully validated!)

(please note that the data in the example are not fully validated!)

Different companies and industries have different opportunities to create positive value. Areas such as volunteering, donations and pro-bono work can make a big difference and are relatively easy to target and measure. When it comes to the goods or services the company offers, it is often more difficult to measure the positive impact, especially if we also strive for a measure that can be compared between companies. Therefore, you may want to focus on what makes sense for your company to follow up and steer – manage – towards.

When we tested this among the companies that have been involved in developing the instrument, we quickly realized, for example, that the conscious impact take different forms for the different companies: while the communications agency Spoon wants to work with a larger proportion of assignments that contribute to a sustainable transition, in the case of Tobii Dynavox and Chiesi, it is about their products making as big a difference as possible for the people who need them. In both cases, it can be measured and followed up, but it is not that easy to compare companies.

At the same time, the process of identifying tools for follow-up contributes to an important discussion about what the company’s additional, positive impact is and can be. And in some cases, also with how different goal conflicts should be handled: Can the positive impact the company has on society and people warrant a slightly lower return? Or to what extent can a positive impact on humans also “justify” an increase in greenhouse gas emissions? (and vice versa).

3. The company’s indirect positive impact on the surrounding society (Scope 3)

Presumably, all companies have some type of indirect positive impact. Perhaps the “easiest” example is through the taxes companies pay and the fact that they provide livelihoods for people. In some cases, the results of taxes and jobs may be marginal, but for businesses based in e.g. rural areas, the jobs they create are sometimes of vital importance for the survival of communities. And the tax that companies pay, directly or indirectly, is central to the welfare provided by the public sector.

The products or services that companies manufacture often also have what we call an indirect positive impact, even if that is not the reason why the product or service is offered and there is no goal to increase the positive impact for its own sake. An example could be family members who get a better quality of life thanks to medication used by patients, or pedestrians who benefit from cars that make less noise. These are examples that there may be value in reporting, i.e. communicating, even if it does not mean that the company actively directs its energy to increase this positive impact. In the event that the company starts to steer its operations to increase this indirect impact, in the Triangle of Impact, it moves towards becoming direct (i.e. Scope 2).

This third scope is, almost by definition, difficult to delineate and it therefore becomes a bit of an “other” item in the model. The reason for still using this scope is that the process of identifying the indirect impact can also make the company realize that there is some indirect impact that they actually want to work more with. In addition, it is an area that both internal and external stakeholders are often interested in.

The next step, or “How do I get started?”

“The Triangle of Impact” is not fully developed as a model, but hopefully it is ready enough for companies that are looking for ways to take their sustainability work further, and in particular their social sustainability work, to be able to work with or be inspired by the model. My, or our, hope is that we will continue to work with the different components of the model, both the communicative (because the model is also a way of communicating one’s work) and the governance aspects. Thus, the model can hopefully contribute to making it a little easier both to adapt your business to increase the positive impact, but also to benefit from the work that is already being done! So what can you do? Start by looking at the scopes and ask yourself what your impact is – and what you want it to be. And don’t hesitate to contact We-ness or any of the other companies that took part in developing the Triangle of Impact.

If we feel that there is a great demand, we will probably develop this short introduction further, to become a “handbook” where we develop the process for those who want a clear roadmap to stick to, supplemented with inspiring examples.

———————-

* For many years, I have worked to find solutions to extremely serious social problems, especially poverty and oppression in so-called developing countries. Often, it has been about support for states to build their own capacity to, for example, establish a relevant system of education that reaches as many people as possible, or about support for human rights defenders in civil society – or, for that matter, about more urgent support through organizations such as the Red Cross or the UN. As it has become increasingly obvious that the world’s challenges will not be solved by states, I have come to work more and more with the business community. I am convinced that the commitment and innovation that exists in the business community is crucial for a transition towards a better, more sustainable society. And we can do much more than “do no significant harm”. Milton Friedman was, in my view, wrong when he wrote in 1970 that the sole responsibility of corporations is to generate returns for their owners. (read his famous article in the NY Times in this link). The companies I work for can and want more than that!