Detta blir mitt sista nyhetsbrev i detta format. Efter sommaren börjar jag en tjänst som Generalsekreterare för Hand in Hand Sweden. Det kommer ge mig möjlighet att arbeta väldigt konkret med entreprenörskap som ett verktyg för hållbar utveckling (läs mer här). Jag vill därför tacka alla mina följare, kunder och andra partners för denna tid, och hoppas att vi ses eller hörs även framöver.

Det är nu snart sex år sedan jag blev egenföretagare. En utgångspunkt för mig har varit de möjligheter företag har att bidra till ett bättre samhälle och en friskare planet. Och, bör jag lägga till, de skyldigheter som numera följer med att bedriva företag. Varken stater, civilsamhälle eller företag kan ensamma förväntas lösa klimatkrisen, fattigdom, ojämlikhet eller utanförskap. Det är ett gemensamt projekt där många – väldigt många – människor och organisationer behöver delta. Därför valde jag att ge mitt företag namnet ”we-ness”. Vi är i skiten tillsammans, så att säga. Men än viktigare, vi kommer behöva ta oss ur den grop vi grävt tillsammans.

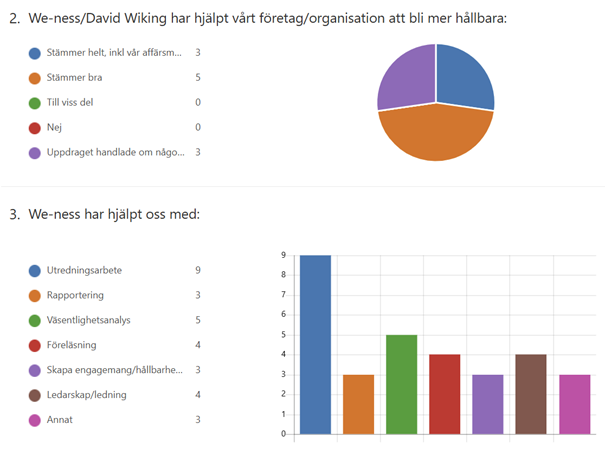

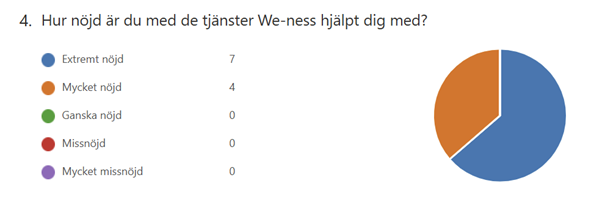

Sex år med spännande uppdrag. Mängder av lärdomar, möten och samarbeten. Jag hade höga förväntningar och det blev bättre än vad jag tänkt mig. Jag har kanske inte räddat världen men jag har i alla fall försökt vara en del av en positiv utveckling.

Här är en kort sammanfattning av några av de slutsatser jag dragit under mina år som rådgivare till företag som velat ställa om i en mer hållbar riktning – och även till myndigheter och andra som varit intresserade av hur samverkan med näringslivet kan bidra till en mer hållbar utveckling. Varje punkt har utvecklats i tidigare hållbarhetsbrev, för den som vill gräva vidare.

Företag och företagare är en förutsättning för omställningen

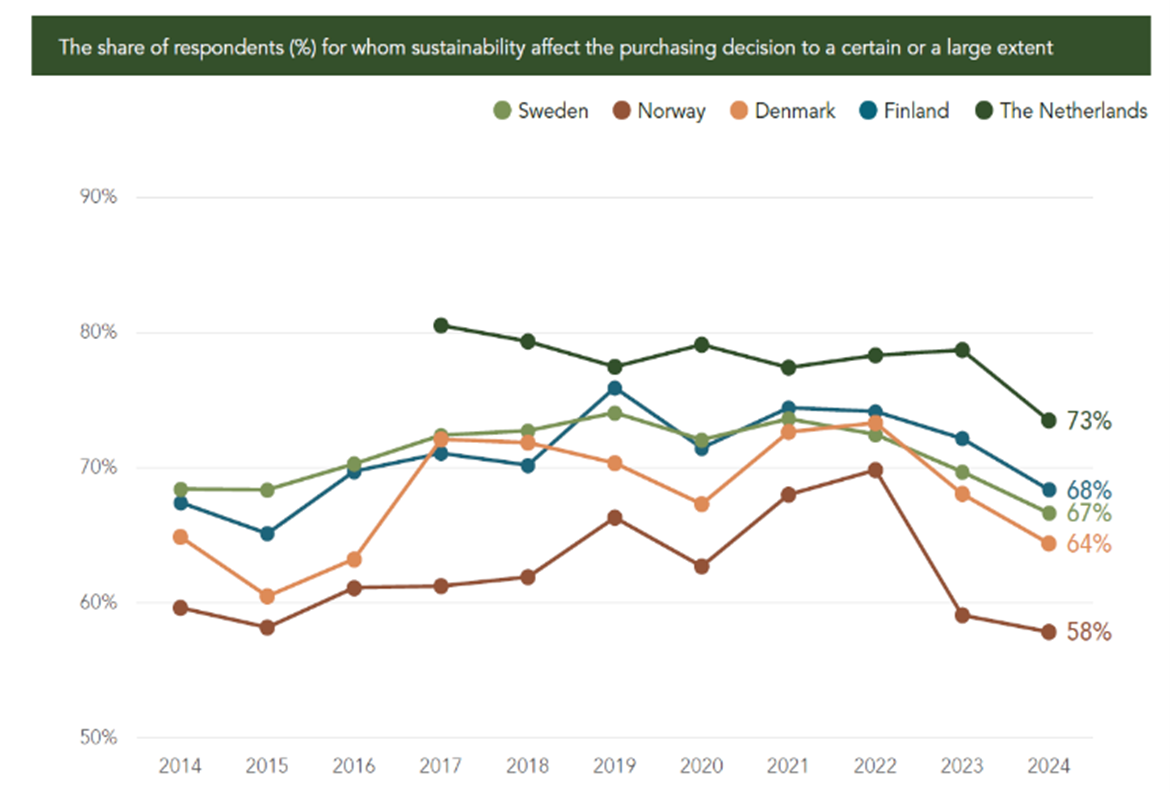

Vår ekonomi bärs upp av aktörer inom näringslivet. Med rätt förutsättningar kan de uträtta storverk. Ibland behövs lagstiftning som hjälper till, men efterfrågan från kunder och anställda börjar bli så påtaglig, att det ofta finns ett rent affärsmässigt incitament till att arbeta med hållbarhet, oaktat den piska och morot som följer av regleringar. Dessutom har jag de senaste åren upplevt ett allt större intresse för hållbarhet från ägare. Ibland just som en följd av regleringar och efterfrågan från kunder, men det är inte heller ovanligt att ägare och företagsledningar faktiskt vill vara en del av lösningen.

Hållbarhet som strategi – inte som tillägg

Hållbarhet bör integreras i företagets kärnverksamhet, inte behandlas som en separat aktivitet. Det innebär att ESG-aspekter (miljö, socialt ansvar och styrning) ska knytas till affärsmodellen, strategin och beslutsfattandet. Med det sagt; det räcker sällan med att gå från en hållbarhetsstrategi till en hållbar strategi. Det behövs också en företagskultur och ett vettigt ledarskap för att åstadkomma en mer djupgående förändring. Kompetens däremot, är enklare att kompensera för.

Cirkulär ekonomi – från avfall till resurs. Men det går för långsamt

Under de år jag arbetat med hållbarhet har behovet av en mer cirkulär ekonomi ofta lyfts fram som mer eller mindre nödvändigt för en grön omställning. Det handlar om att gå från linjära till cirkulära affärsmodeller, genom att inte minst designa produkter och processer så att resurser återanvänds och avfall minimeras. Jag hade nog trott att fler företag skulle ha anammat cirkulära affärsmodeller, än vad jag upplever är fallet. Kanske beror tvekan på att politiken (och då tänker jag inte bara eller ens i första hand på Sverige) inte helt ställt sig bakom denna del av omställningen.

Social hållbarhet – vi kan bättre

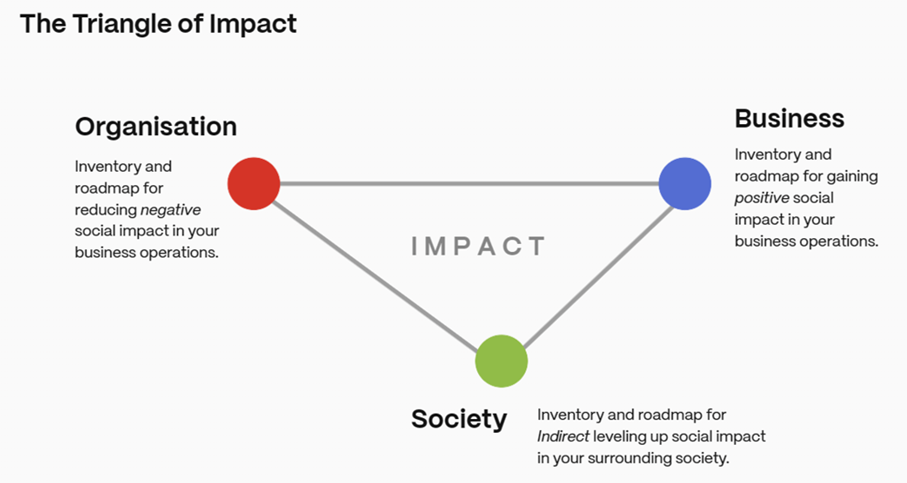

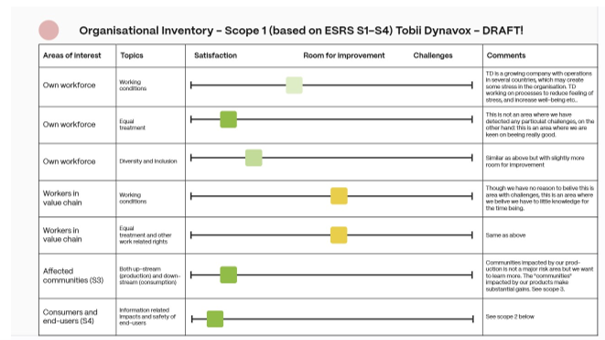

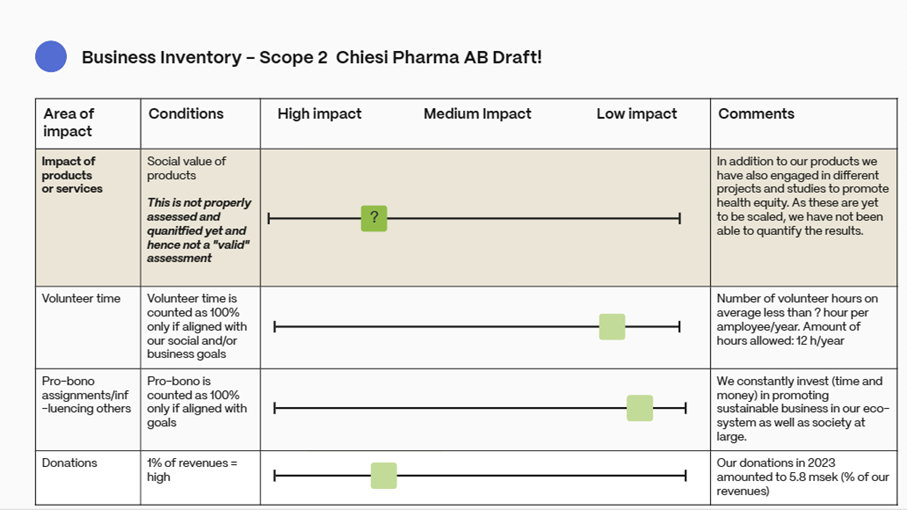

För företag innebär social hållbarhet att ta ansvar för hur verksamheten påverkar människor – både anställda, kunder och samhället i stort. Det kan innefatta att främja goda arbetsvillkor, mångfald och inkludering, samt att bidra till lokalsamhällets utveckling och respektera mänskliga rättigheter i hela värdekedjan. Men företag har ofta svårt att mäta sin sociala hållbarhet (undantaget den egna arbetskraften). Det gör också att det värde som företaget kan skapa avseenden sociala hållbarhet ofta förbises. Dessutom stannar analysen ofta vid att minska den negativa påverkan, snarare än att medvetet öka den positiva. I takt med att välfärdsstaten inte längre kan tas för given på samma sätt som tidigare, i kombination med ett ökat intresse hos företag att (likt många amerikanska företag) faktiskt bidra positivt till lokalsamhälle, ser jag ett ökat intresse för nya företagsformer som ”benefit corporation” liksom andra sätt att skapa ett “shared value” – där både företaget och samhället gynnas.

Hållbarhetsrapportering – transparens och trovärdighet, men glöm inte lärandet!

De senaste åren har vi sett ökade krav på hållbarhetsrapportering, inte minst genom CSRD och EU:s taxonomi. Brist på standardiserade kriterier, får man anta att reglerarna tänker, kan leda till otydlighet och förvirring och ifrågasättande av olika certifieringars trovärdighet. Att EU nu backat avseende omfattning och vilka som ”träffas” av lagstiftningen är visserligen försåtligt av flera skäl, men också riskabelt ur ett makroperspektiv. Argumentet är att minskade krav och minska byråkrati ska öka euroepiska företags konkurrenskraft, men på sikt är i alla fall jag övertygad om att hållbarhet i sig är en konkurrensfördel. Dessutom möjliggör klok rapportering ett utmärkt tillfälle för lärande. Därutöver skulle jag gärna önska att fokus i praxis och lagstiftning förskjuts mer åt frågor som är materiella (väsentliga) för företagen och där de har en reell påverkan.

Så till sist: Hållbar utveckling förutsätter hållbara företag och för de som ligger långt fram är Agenda 2030 fortfarande ett värdefullt verktyg!

Global hållbar utveckling är inget vi kan överlåta till politiken ensam — den kräver att företag tar aktivt ansvar. Agenda 2030 var kanske inte ett startskott men i flera avseenden kom den att bli en katalysator och en utgångspunkt för många företags ambition att vara en del av lösningen på samhällsutmaningar. När affärsmodeller byggs på långsiktighet och väver in mänsklig värdighet och respekt för planetens gränser, blir företagen en kraft för verklig förändring. Hållbara företag ser inte vinst endast som mål, utan också som ett medel för att skapa värde för många. Det är i samspelet — i ett “we-ness” — mellan människor, samhällen och näringsliv som framtidens lösningar växer fram. Utan hållbara företag, ingen hållbar framtid.

Tyvärr tycks Agenda 2030 ha blivit omodernt, något jag har viss förståelse för (ibland kom det att bli en ”pricka-av”-övning), men samtidigt beklagar. Jag har skrivit om det tidigare så ska inte upprepa mig, men jag tror att Agenda 2030 hade kunnat utvecklas till att bli ett spännande verktyg för de företag som strävar efter ”impact” utöver att minska sin negativa påverkan.

Med dessa rader avslutar jag detta sista nyhetsbrev. Håll gärna kontakten med mig på LinkedIn eller annat sätt. Och de som vill kan säkert följa mig på Hand in Hands olika kanaler.

Tack!

uppoffringar? Om detta beror på en tveksamhet inför om det egna handlandet har någon större påverkan, om det är okunskap, minskat ekonomiskt utrymme eller rent av själviskhet vet jag inte (sannolikt beror det på. För en mer filosofisk diskussion kan

uppoffringar? Om detta beror på en tveksamhet inför om det egna handlandet har någon större påverkan, om det är okunskap, minskat ekonomiskt utrymme eller rent av själviskhet vet jag inte (sannolikt beror det på. För en mer filosofisk diskussion kan

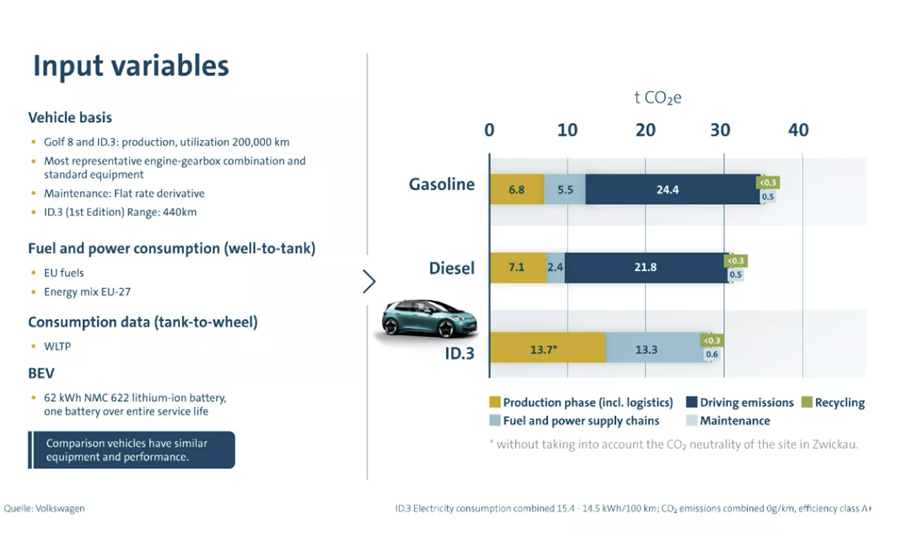

(please note that the data in the example are not fully validated!)

(please note that the data in the example are not fully validated!)